Welcome To A La Niña Winter

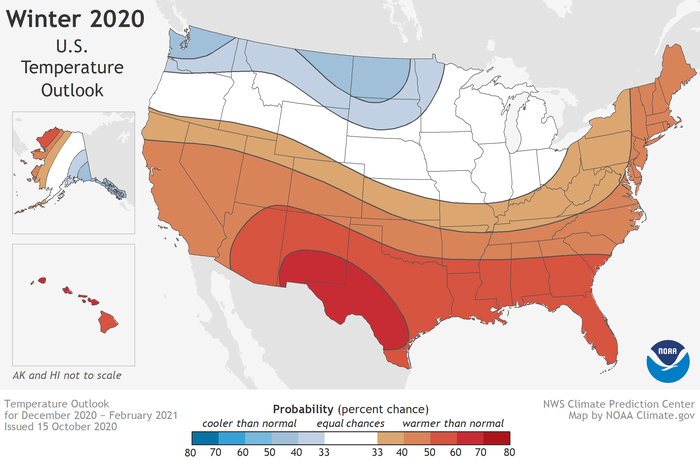

According to recent data from the Climate Prediction Center, CPC, La Niña is in full swing, with good chances of it staying in place through March 2021. Here's a look at what this might portend with our average Colorado weather this winter. These are the latest climate maps for the next month, from the CPC.

Most of us are familiar with El Niño, and La Niña. These are opposing conditions in what is called the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. This is a climate phenomenon; one of many across the planet. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, and other research organizations have been studying these for many years, and observing their effects on precipitation and temperature. ENSO isn't just an ocean temperature thing. It is also tied to ocean currents.

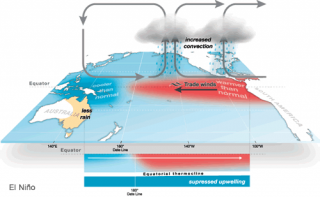

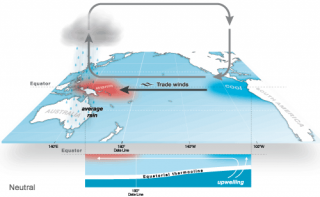

ENSO has three main phases. They are El Niño, La Niña and Neutral. There are also sub-phases like "mild" or "strong". During the neutral phase, sea surface temperatures are distributed more evenly, with no dominant cold or warm areas in the Pacific, and minimal effect on the ocean currents and weather patterns.

The CPC started seeing indications last summer of an approaching La Niña condition. Now that sea surface temperatures and other data have confirmed the situation, a "La Niña Advisory" has been issued by the CPC.

From their powerpoint presentation of November 16, 2020: "La Niña conditions are present. Equatorial sea surface temperatures are below average from the west-central to the eastern Pacific Ocean. The tropical atmospheric circulation is consistent with La Niña. La Niña is likely to continue through the Northern Hemisphere winter, 2020-2021." They indicate a 95% chance that La Niña will be present from January through March, and a 65% chance of it continuing into spring of next year. NOAA and other scientific agencies not only measure sea-surface temperature, but also at various depths. Likewise, while surface winds are measured, wind direction and speed are also measured higher up, in order to confirm the conditions.

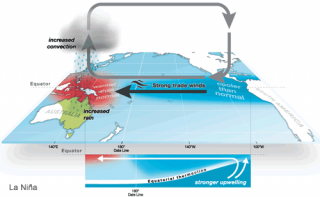

During La Niña, the colder ocean water over the Eastern Pacific will tend to cause an east-to-west flow of air along the Equator. This is because cold air is more dense, with higher surface pressure, and will tend to flow toward lower pressure. The movement of air also contributes to the movement of the ocean water below, and vice-versa, in a feedback loop. With La Niña, wind blowing from east to west will evacuate water from the Eastern Pacific. So, colder water from below will rise up to replace it, causing a the loop which continues until the pattern is disrupted.

The ENSO affects Colorado and much of the United States differently, depending on the phases. Generally speaking, an El Niño brings cooler air and better precipitation chances to Colorado. During an El Niño, we have warmer water in the Eastern Pacific, and colder water to the west. This setup causes equatorial winds to converge in the ocean, resulting in rising air, (convection), which translates into favorable conditions for precipitation for much of the western U.S., including Colorado.

With La Niña, the opposite is generally the case, with air subsiding, or sinking, causing less cloud cover, and an unfavorable precipitation scenario.

So that's how the ENSO system works. What does this means for our Colorado winter season, especially in terms of precipitation?

We've had two full-on La Niña winters recently, netting the lowest precipitation averages, at least since records have been kept in Denver. Keep in mind, that these are averages, and do not account for individual events. Denver's average snowfall is just over 56 inches, and during the past two La Niña years, we've averaged 21 to 26 inches. This doesn't mean we can't get the Mother Of All Snowstorms, but on-average, precipitation totals are lower.

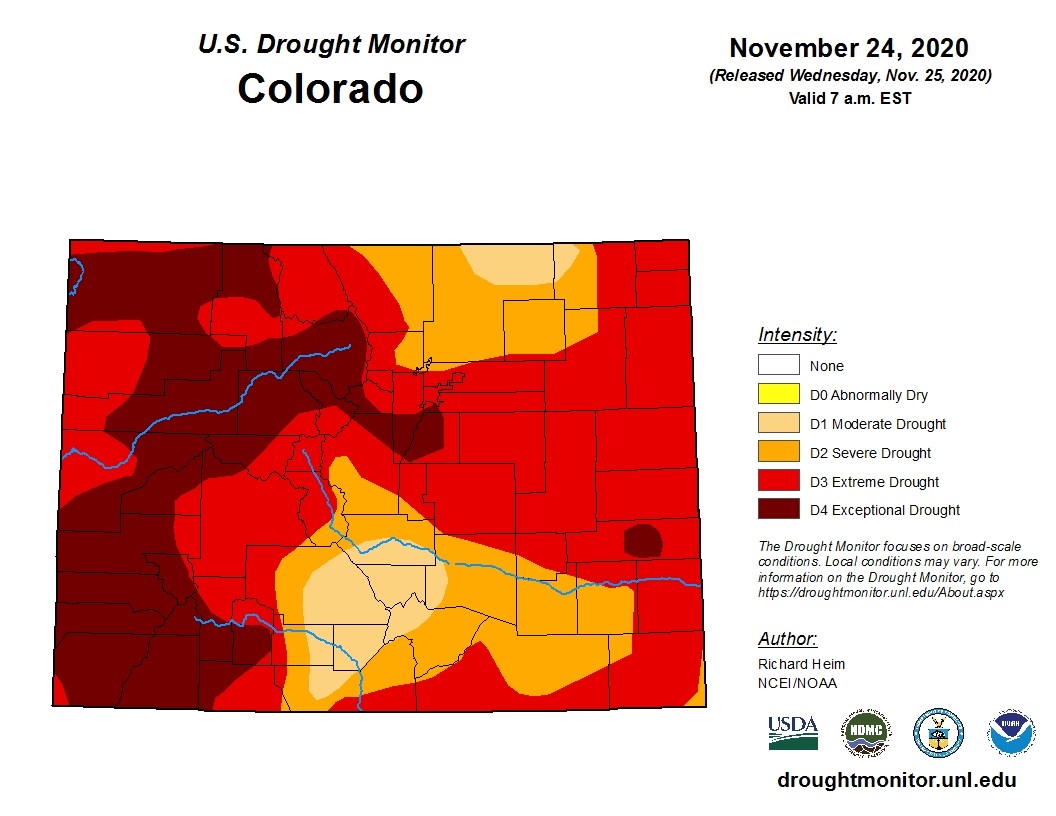

The decrease in precipitation during La Niña years isn't restricted to Denver. Most of the southwestern states experience the same conditions - lower than average precipitation, and higher than average temperature.

One of the main concerns is obviously the mountain snowpack. The whole state is experiencing some level of drought, much of it severe.

La Niña isn't all bad news for the Colorado mountains. In other words, the warmer, drier conditions usually experienced in Denver and on the plains, doesn't always translate to our higher elevations. Mountain snowpack may stay near-average, or even above, this winter.

One other observable La Niña trend for Colorado is occasional blasts of cold Arctic air, punctuating the generally warmer conditions. These come in the form of cold fronts, which come down through the Northern Rockies and into our plains, with usually lower snowfall amounts, gust wind, and very cold temperatures. We've already seen a few of those this season.

ENSO affects temperature and precipitation across most of the country, so it is a large scale circulation with widespread effects, as shown on the first two maps.

To summarize, the news is not great for Colorado precipitation totals this winter. However, La Niña isn't the sole determining factor. There are many other oceanic circulations, which are "teleconnected" or "interwoven" in the scheme of worldwide weather patterns. So a La Niña winter doesn't necessarily mean a very dry winter. If you remember the "Super" El Niño from a few years ago, predictions of snow totals for Colorado were huge, and that did not pan-out.

The science behind this, based on observations, is relatively straightforward, but it does not predict the future. El Niño and La Niña produce trends. Sometimes they fit the model, and sometimes they don't. And obviously, weather is not an exact science. It's very hard to convert air molecules into numbers.

If you wish to keep track of daily precipitation in Colorado, or anywhere in the country, there is free data, supplied by volunteer observers, at www.cocorahs.org. For now, it's "wait and see". We know the trends. Let's hope for at least average precipitation over the winter in our very dry state.

In the meantime, we'll keep you updated on your local weather with our daily mountain forecasts by Chief Meteorologist Steve Hamilton, where you can also find our interactive radar map, and on breaking severe weather alerts in our Scanner & Emergency Info, Weather Forecasts Forum to which you can Subscribe for instant email alerts. Check current weather and road conditions using our exclusive webcam pages!

For the podcast version of this article, please click here!